Here’s why, and what you can do about it.

Steep Internet bill and no choice? If you live in an apartment building, the landlord might be profiting from your plight.

Exclusive broadband agreements between apartment building owners and internet providers in cities like Los Angeles are common, leaving renters with no choice but to pay inflated costs for sub-par service — and rewarding landlords for keeping it that way.

The existence of these exclusive arrangements is surprising for a simple reason: they were outlawed eight years ago .

So how are they getting away with it? Why are landlords getting such a big cut? And most importantly, what can renters do about it?

How landlords get their cut of your broadband bill

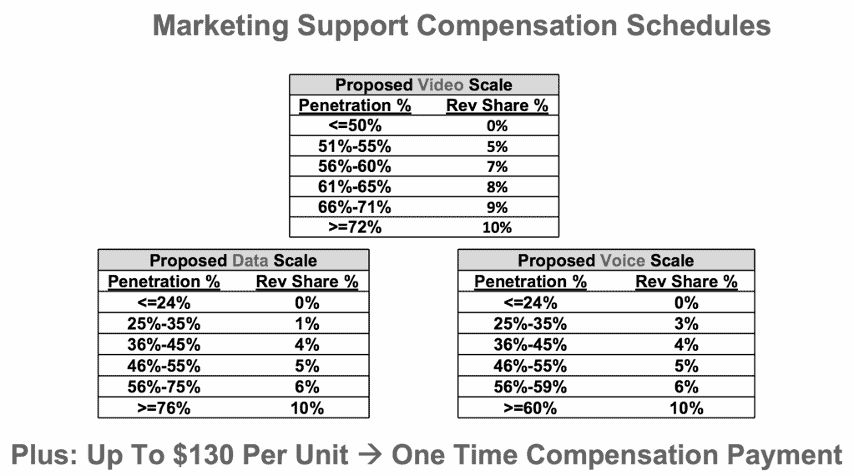

Before the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) outlawed them in 2008, revenue shares and long-term contracts between ISPs and MDUs (Multiple Dwelling Units) were perfectly legal. They were even advertised openly on company websites .

Current regulation may stop ISPs from creating exclusive contracts — but it doesn’t stop MDU owners from controlling who can enter to install wiring. As a result, landlords can sneak around the law by simply shutting the door when a competing ISP comes knocking.

…And you can bet your bottom dollar the ISP they do allow in is paying for the privilege.

Types of exclusive agreements

Apartment building Internet monopolies come in three flavors:

1. Door fees

Door fees are exactly what they sound like: arrangements where a building owner charges fees to enter the building.

Door fees generally take the form of revenue shares, but flat rates for access are also common — and more than sufficient to deter competing ISPs from entering the premise. In an interview with Crain’s, Shrihari Pandit of Stealth Communications reported that building owners in Manhattan often charge in the thousands per month:

We’re not cutting into the building, not drilling, just using existing conduit, but they want to charge us $1,500 a month to bring in this tiny cable .

2. Revenue shares

Revenue share arrangements are also straightforward (if not strictly legal): an ISP offers building owners a percentage of revenue from subscribers in their building. The more subscribers, the higher the share — incentivizing landlords to work against competing ISPs and prevent renters from gaining bargaining power.

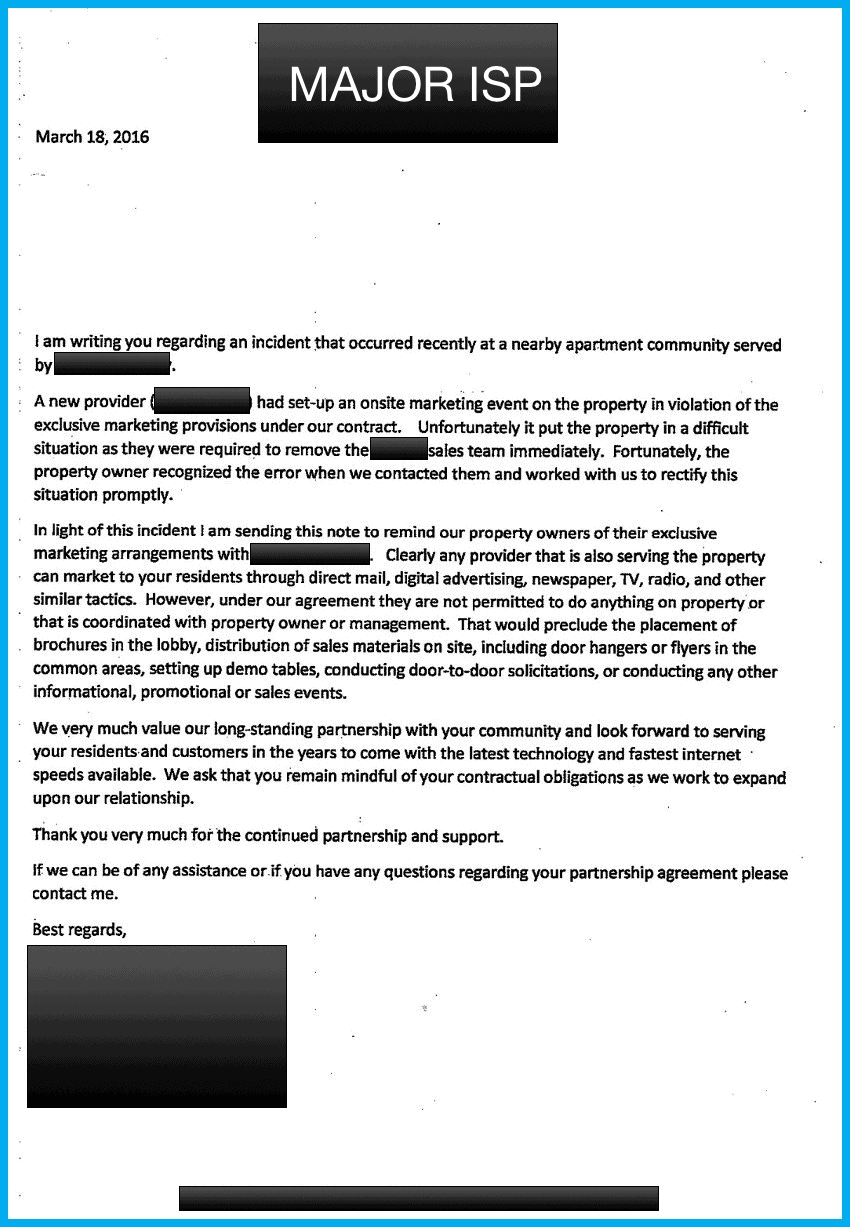

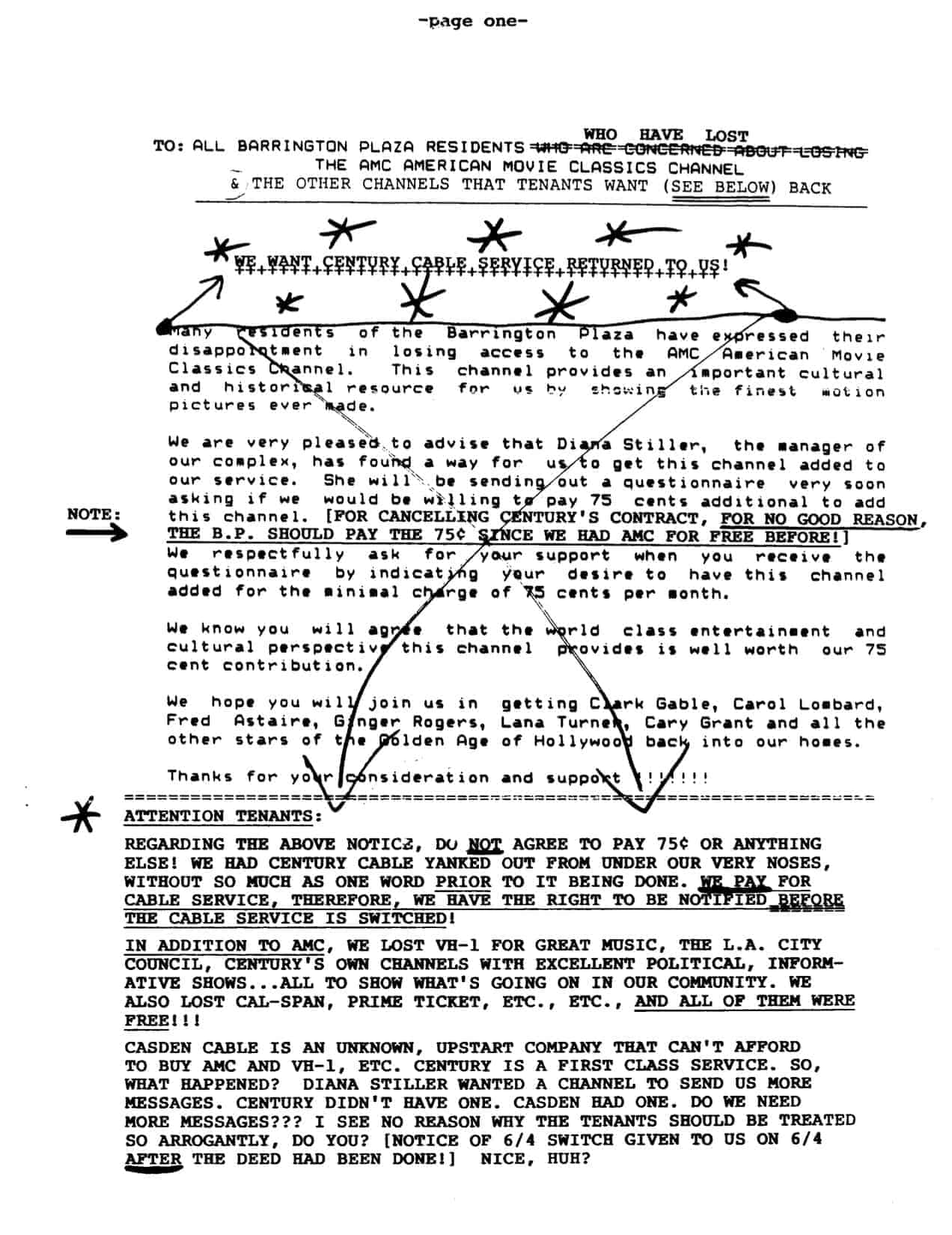

3. Exclusive advertising agreements

Ever left your apartment to find complimentary donuts and coffee in the lobby, or find pamphlets advertising special offers from a competing ISP on the doormat? If not, it may be because your landlord keeps them out. Sure, exclusive service agreements are legally iffy. Exclusive advertising agreements, on the other hand, are perfectly legal.

As a result, competing ISPs are out of luck if they want to knock on your door and offer a better deal. Take this letter, for example, delivered to a building owner who violated their exclusive advertising agreement with a major ISP:

Helpful resources: FCC Regulation that affects Internet access for apartment renters

The inside wiring problem: who owns the “pipe” that delivers Internet?

At the heart of all this legal trickery is a single object: the wire that connects your apartment to the Internet.

Inside wiring is expensive to install, and the government isn’t exactly jumping to foot the bill for universal, shared public infrastructure. The FCC is stuck trying to regulate who has what rights when it comes to installing, using, and removing these wires.

Unfortunately, the laws are riddled with interesting loopholes.

First off, the regulations start to fall off when the inside wiring isn’t technically owned by the ISP:

The provisions do not apply where the cable home wiring belongs to the subscriber, such as where the operator has transferred ownership to the subscriber, the operator has been treating the wiring as belonging to the subscriber for tax purposes, or the wiring is considered to be a fixture by state or local law in the subscriber’s jurisdiction.

…Second, passing that ownership from renter to building owner is no problem:

The MDU owner shall be permitted to exercise the rights of individual subscribers under this subsection for purposes of the disposition of the cable home wiring under § 76.802.

Basically, whoever owns the cables calls the shots on entry and installation — and manipulating who owns the cables is straightforward. Once the landlord has the wires, they can simply set up an exclusive license back to the ISP .

It’s actually kind of brilliant.

Exclusive broadband deals impede fair market competition

Consumers aren’t only ones hurt by all this — smaller ISPs also feel the burn. Here’s Charles Barr of Webpass (an ISP recently acquired by Google Fiber) in an interview with Professor Susan Crawford:

The FCC’s rule is nonsensical. They’re saying you can’t have exclusive agreements, but, at the same time, a landlord gets to say yes or no to anyone coming into the building, and you have to have the landlord’s permission. So, a landlord certainly can sign an agreement with one company and say ‘No’ to everybody else, thereby creating an exclusive agreement. So that’s what they do. They’re under no obligation to let everyone in, so they’ll extract a rent payment from one provider.

Broadband expansion in urban areas will be crippled until this problem is solved. In the meantime, small ISPs are stuck in their current positions as niche providers in predominantly rural areas.

In a roundabout way, even the landlords are losing money to exclusive broadband agreements. Competitive broadband options are shown to raise rent value perception as much as 8%. Consumer surveys conducted as recently as June 2016 found fast, reliable broadband to be the single most important amenity for apartment dwellers . Another study found that gigabit fiber connections can push rent profits even higher, up to 11% .

Long story short, many landlords could easily profit by ending their de facto exclusive agreements and encouraging broadband competition. Tragically, confusion about how broadband works combined with the difficulty of wading through dense FCC regulation means nothing is likely to change — unless consumer demands, regulation, or increased competition step in to fix it.

Who should own inside wiring?

The journey between your cable jack and the base of your building may be short, but it’s a road lined with legislative failure.

Like all broadband issues, the story isn’t entirely black and white.

ISPs have a legitimate claim to the wires, since they paid up front to have them installed. Why should another ISP be able to “piggyback” on their network?

Landlords, meanwhile, have a legitimate right to stop private companies from meddling with their buildings. Why should any company offering internet be allowed to enter the building and make alterations like drilling in wires, poking holes in floors, etc.?

Renters have a legitimate right to internet at a fair price, regardless of who “owns” the wires, since it’s classified as a utility like water or electricity. Home Internet access is increasingly essential to quality of life and equal opportunity , rather than a luxury like television.

Internet infrastructure — a hodgepodge of private and public fiber networks hooked up to re-used television and phone networks — isn’t ideal for anybody. Short of government-funded neutral infrastructure, it’s difficult to imagine a “perfect” situation that serves ISPs, landlords, and renters equally.

Here’s what consumers can do to protect their interests:

The complex legality surrounding Internet access makes going to court costly and risky for renters. Court cases against landlords manufacturing monopolies have been successful in the past , but less drastic action is more realistic for the average renter.

Here are some steps consumers can take to protect themselves from apartment building broadband monopoly traps:

1. Check before you sign

Before you sign a lease, manually check what Internet providers are available. Start with a broad zip code search using the BroadbandNow internet service provider search tool, then follow up by calling each provider to check if they can access your specific building.

2. Ask your neighbors

Introduce yourself to your potential neighbors, and ask what options they have.

3. Tell landlords how you feel

If you don’t move into a building because of a lack of broadband choice, inform the owner so they’re aware that choice matters to renters.

4. Participate in local government

Be active in your local government, and ask your representatives to support pro-competition broadband initiatives like dark fiber.

5. File a complaint

A critical mass of public complaints can have an impact. You can file with both the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) and FTC (Federal Trade Commission):

- FCC consumer complaints center

- FTC complaints form for individual consumers

Regulatory changes that could solve the issue:

- Make denying entry to ISPs illegal. Hong Kong did it, and so can we .

- Require new buildings be fiber-ready. European cities like Paris already do this, along with some municipalities in California .

- Require building owners to maintain neutral wireless facilities.

- Make revenue shares and door fees illegal in all forms.

The big picture:

The combination of a limited housing market with an uncompetitive broadband market is a recipe for consumer disappointment.

70% of world pop will live in cities by 2050, and that means more apartment dwellers… a lot of them. The number of rentals in the US has increased by over 700,000 per year since 2004. That trend promises to continue as cities grow. Problems accessing broadband will only grow if not addressed by regulation, free market competition, or some combination of the two.

In the meantime, the best we can do is stay educated about our rights and refuse to sign contracts that bend the law.