Editor’s Note: This article has been updated.

It appears as though Joe Biden has signalled his support for Net Neutrality through his “unity task forces” with Bernie Sanders, stating that “Democrats will restore the FCC’s clear authority to take strong enforcement action against broadband providers who violate net neutrality principles through blocking, throttling, paid prioritization, or other measures that create artificial scarcity and raise consumer prices for this vital service.”

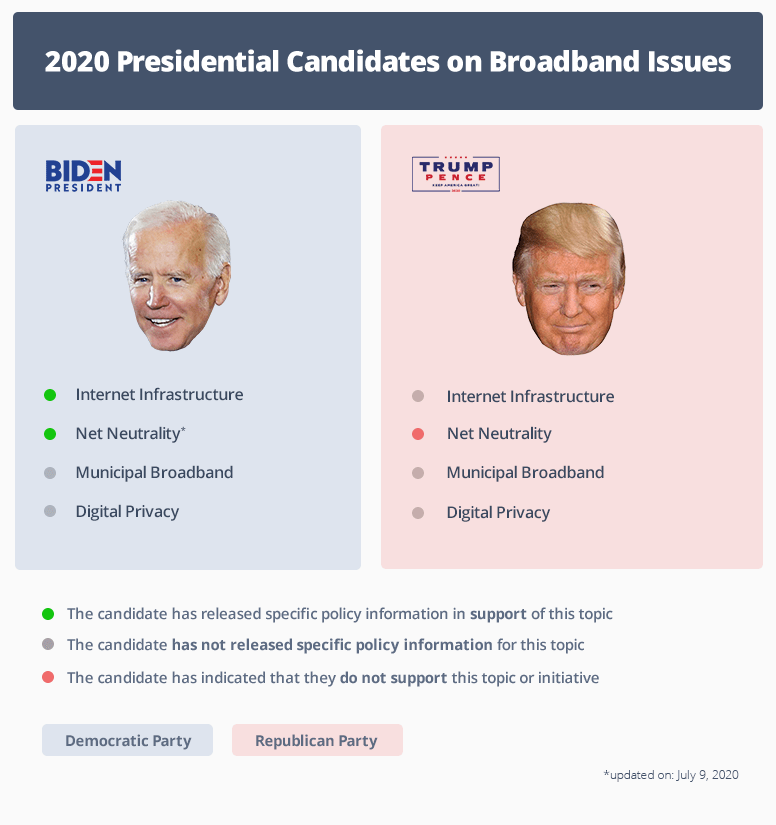

As the nation enters the final lead-up to the November 2020 general election, one of the most important points of contention emerging as a result on the ongoing coronavirus pandemic is the digital divide that persists across swaths of the nation, leaving millions of Americans without broadband. As we continue to balance working and learning from home in many parts of the country, the question is more timely now than ever before: what will it take to close this longstanding divide once and for all? This question, it seems, depends heavily on who will be President in 2021 and beyond.

Key Broadband Issues

Across the country, broadband policy is taking center stage as the coronavirus pandemic continues to unfold and millions of Americans remain without a reliable way to get connected from home. As we enter the final stages of the 2020 election, here is where the two primary candidates stand on key broadband policies.

Internet Infrastructure

U.S. internet infrastructure significantly lags behind other highly-developed nations — even in major cities like San Francisco and Dallas — and this disparity is a direct threat to the nation’s continued ability to exert its influence and remain competitive within the emerging industries of tomorrow. Here’s how the 2020 candidates compare on the issue of infrastructure improvement in the U.S.

Donald Trump

One of the Trump campaign’s key promises in the 2016 election was to expand broadband availability in rural areas. Since then, his administration has made efforts to do so through various executive orders, allocating $600 million in 2017 meant to expand infrastructure deployment through a USDA pilot program. In 2019, the Trump administration rebranded an existing program into the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund, which promises $20.4 billion meant to support the deployment of rural broadband over the next decade. Though a fresh name was applied, the money was already in place from years prior.

Beyond these more evolutionary steps, little has actually been done to bring broadband to the more than 42 million Americans that may currently lack a broadband connection today. A $1.5 trillion infrastructure bill was proposed in 2018 by the White House, but ultimately went nowhere in Congress. The bill had earmarked $50 billion for rural communities, albeit for a variety of purposes not at all exclusive to broadband infrastructure. Because it left the details to state officials in terms of how and where to spend the money, it was never clear how much would ultimately end up going toward broadband deployment.

Now the President’s reelection campaign is again promising to push a $1 trillion infrastructure bill through Congress in the wake of the economic damage the ongoing pandemic has caused across the country. The bill will reportedly include money for 5G and rural broadband deployment, but no further details have been provided, making the Trump campaign’s specific plans for closing the digital divide unclear.

Joe Biden

Joe Biden announced a $1.3 trillion infrastructure bill last fall that included $20 billion for rural broadband expansion. Biden’s campaign has said that “Rural Americans are over 10 times more likely than urban residents to lack quality broadband access. At a time when so many jobs and businesses could be located anywhere, high-speed internet access should be a great economic equalizer for rural America, not another economic disadvantage.” The campaign website also claims that the investment could create as many as 250,000 new jobs.

Like the incumbent President’s proposals, Biden’s are light on specifics. It is unclear how a potential Biden administration would tackle the challenging problem of delivering robust broadband to America’s hardest-to-cover areas, nor is it clear how long it might take to do so. That said, the Biden campaign has said that “High-speed broadband is essential in the 21st Century economy,” and signaling intent to work with municipal providers to bring access to all Americans is a tangible step in the right direction.

Net Neutrality

In the past, Net Neutrality rules have prevented major ISPs with media operations like Comcast, Spectrum, and AT&T from favoring some content over others, and ensured that they couldn’t throttle traffic to certain services or prevent users from accessing certain sites. Net Neutrality became a hot-button partisan issue after Obama-era FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler designated broadband a utility and subjected ISPs to regulation. The move received widespread criticism from the telecom lobby and the Republican party, and president Trump’s FCC chairman Ajit Pai repealed the rule in 2017.

Donald Trump

Donald Trump and his administration do not support Net Neutrality. The President made repealing the protections put in place by the previous FCC Chairman a top priority in 2017, and was ultimately successful in doing so after threatening to veto the Save the Internet Act, which was a bill aimed at preserving the Title II protections by codifying them into law.

Additionally, the administration has previously sued the state of California in an attempt to block the state from implementing its own Net Neutrality laws in 2018. The courts upheld the FCC’s overturning of the national laws, but ultimately declined to rule that states could not create their own protections.

Joe Biden

JULY 9TH UPDATE: It appears as though Joe Biden has signalled his support for Net Neutrality through his “unity task forces” with Bernie Sanders, stating that “Democrats will restore the FCC’s clear authority to take strong enforcement action against broadband providers who violate net neutrality principles through blocking, throttling, paid prioritization, or other measures that create artificial scarcity and raise consumer prices for this vital service.”

Original text: Joe Biden has never been an outspoken supporter of Net Neutrality. He is reported to have stated back in 2006 that he did not believe preemption laws were necessary to protect the neutral landscape of the internet, and one year later, he declined to co-sponsor the Internet Freedom Preservation Act, which was a bipartisan bill that aimed to amend the Communication Act of 1934, including net neutrality protections in the process.

Additionally, the former Vice President also kicked off his 2020 election campaign last year with a fundraiser hosted by David Cohen, one of the top lobbyists at Comcast (a longtime opponent of Net Neutrality).

Municipal Broadband

Across the country, many cities and towns that have long been underserved by the private sector have turned to building and managing their own broadband networks in order to serve residents directly. The issue has become a partisan one in recent years, with some Republicans calling such initiatives “government overreach.”

Donald Trump

Donald Trump’s reelection campaign has not presented a firm stance for or against the concept of community-driven broadband for 2020. That said, his FCC administration has taken concrete steps to prevent municipalities from regulating broadband within their respective communities, and the federal organization has not made community broadband initiatives a key component of their rural broadband plan, to date.

Joe Biden

Biden’s campaign has also not articulated its official stance on municipal broadband as a concept. However, the campaign’s rural revitalization plan includes efforts to triple the Community Connect broadband grants, which includes the opportunity to partner with municipalities and electrical cooperatives to provide broadband to residents, so it would appear that a Biden administration may be friendlier to municipal regulation than the current one.

Digital Privacy

Issues of digital privacy have been on the rise in recent years, spurred on by a series of high-profile data leaks, lawsuits, and accusations of foreign influence in domestic affairs. States have begun enacting their own protections, like California’s CCPA (California Consumer Privacy Act), and as we look toward a future increasingly reliant on the internet, how we protect citizens’ fundamental rights to privacy has become a key discussion point in the political realm.

Donald Trump

Trump signed a resolution that repealed Obama-era consumer protections that once required ISP’s to obtain customer permission before collecting and sharing data to third parties in 2017. One year later, the administration claimed it was working on a new set of consumer data privacy initiatives.

Despite this, no comprehensive reforms have been made during Trump’s tenure, and the President has repeatedly lashed out at Silicon Valley tech companies over issues like encryption, calling attention to companies like Apple and their refusal to unlock phones containing data that pertained to ongoing criminal trials.

Joe Biden

During Biden’s time in the Senate, he advocated for governmental monitoring of peer-to-peer and telecommunications activity in the name of counter-terrorism. Biden introduced bills that would have banned encryption as a concept. He also wanted to require communications companies to “permit the government to obtain the plaintext contents of voice, data, and other communications when appropriately authorized by law,” in an amendment added to a 1991 counter-terrorism bill.

In 1994, Biden introduced the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA), which required hardware companies to ensure equipment and services were accessible to law enforcement for surveillance. The provision was subsequently expanded to include broadband Internet and VoIP traffic.

However, in recent years, his stance appears to have changed somewhat. He has recently said that the U.S. should look into setting up laws and regulations “not unlike the Europeans” have, presumably referring to the European Union’s robust General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). No specific policy proposals, however, have been made.