The semi-annual FCC Broadband Progress Report is essentially a pass/fail grade for the entire telecommunications industry (meaning ISPs like Comcast, Verizon, etc).

After all, before the FCC can determine how to regulate Internet providers, they have to determine what the big problem areas are.

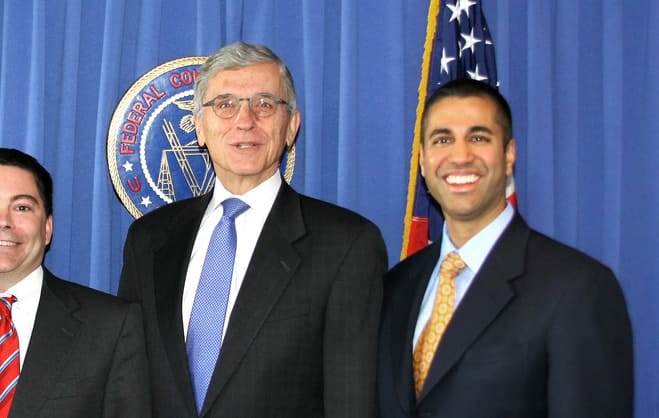

The FCC’s 2018 Broadband Deployment Report is a hot topic this year , since FCC chairman Ajit Pai gave the first “passing” grade to the telecom industry since 2008. This year’s report concludes that broadband in the USA is “being deployed to all Americans in a reasonable and timely fashion.”

Are you a journalist or researcher writing about this topic?

Contact us and we'll connect you with a broadband market expert on our team who can provide insights and data to support your work.

In the chart below, we’ve analyzed every Broadband Progress Report since the report became a requirement in 1999 to show which administrations issued “passing” grades, and which issued “failing” grades. This page will be updated annually.

Broadband Progress Report Results Over Time

| Date | Report Conclusion | Commissioner | President | Report Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | ✅ Pass | Ajit Pai, R | Donald Trump, R | View 2018 Report |

| 2016 | ❌ Fail | Tom Wheeler, D | Barack Obama, D | View 2016 Report |

| 2015 | ❌ Fail | Tom Wheeler, D | Barack Obama, D | View 2015 Report |

| 2012 | ❌ Fail | Julius Genachowski, D | Barack Obama, D | View 2012 Report |

| 2011 | ❌ Fail | Julius Genachowski, D | Barack Obama, D | View 2011 Report |

| 2010 | ❌ Fail | Julius Genachowski, D | Barack Obama, D | View 2010 Report |

| 2008 | ✅ Pass | Kevin Martin, R | George W. Bush, R | View 2008 Report |

| 2004 | ✅ Pass | Michael Powell, R | George W. Bush, R | View 2004 Report |

| 2002 | ✅ Pass | Michael Powell, R | George W. Bush, R | View 2002 Report |

| 2000 | ✅ Pass | William Kennard, D | Bill Clinton, D | View 2000 Report |

| 1999 | ✅ Pass | William Kennard, D | Bill Clinton, D | View 1999 Report |

FCC Broadband Definition Change Over Time

Another factor worth noting is the fluctuating definition of broadband. This has also been a contentious issue in 2017 and 2018, as the FCC proposed adjusting the definition of “coverage” to include mobile LTE service in the 10 Mbps range. This did not make it into the 2018 Progress Report, but the report did include satellite coverage alongside wired for the first time, resulting in much more favorable statistics.

| Date Adopted | Minimum Download | Minimum Upload | Latency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 25 Mbps | 3 Mbps | Not Specified |

| 2010 | 4 Mbps | 1 Mbps | Not Specified |

| 1999 | 200 Kbps | 200 Kbps | Not Specified |

What does the FCC Broadband Deployment Report Accomplish?

The takeaway here is that the 2018 report is the first in ten years to give the broadband industry a passing grade. But what is the actual impact of a pass or fail?

In the past, the report has been used to justify further action to encourage rural and urban broadband options, from creating incentives for ISPs to compete to granting cash payouts from the Universal Service Fund to finance new networks.

Although deployment data since Net Neutrality was repealed is not yet available, the 2018 report maintains an optimistic tone suggesting that the repeal of Net Neutrality and return to “light touch” regulatory policies will result in faster, cheaper, and more widely available broadband in the USA.

When did the FCC Broadband Report become a requirement?

The telecommunications act of 1996 requires the FCC to regularly collect data on the US broadband industry and determine whether or not broadband is being deployed to all Americans in “a timely and orderly fashion.”

This report is important because it has an affect on how universal access funds are distributed, and determines whether or not the FCC needs to create incentives for ISPs to develop in rural areas.

These incentives usually take the form of:

-

- Requirements built into merger agreements

- Network grants from the Universal Service Fund

For example, the much contested Charter and Time Warner Cable merger required the provider to service 2 Million new underserved subscribers in order to get FCC approval. (Being private companies with shareholders to answer too, it’s not unreasonable that ISPs would avoid areas that are expensive to build in, such as rural areas or urban settings with existing incumbent providers.)

The Universal Service Fund is essentially a tax on telecom providers, requiring providers to contribute a percentage of revenue quarterly. In 2016, this amounted to $1.8 Billion. This money is then distributed through projects like E-Rate and the Connect America Fund. We’ve written about abuses of this funding before.

The Digital Divide and Broadband Progress

Media coverage of the 2018 Broadband Deployment Report has focused on the right-leaning wording that seems to credit Obama-era network advancements with the recent repeal of Net Neutrality. The wording of the report is indeed confusing, as it draws a conclusion based on past data rather than data resulting from Trump-era regulatory policies (which won’t be available until Q4 2018 at the earliest).

In our eyes, what’s interesting here is how this report has been leveraged by each FCC chairman to draw attention to their particular policy focus. (In all cases both current and historical, “passing” conclusions have always come with caveats about the need for rural improvement attached.)

Tom Wheeler, for example, never granted a passing grade and appeared to use the report as a means of drawing attention to the failure of telecoms to serve all Americans. Pai, on the other hand, seems to be passing blame on to left-leaning Net Neutrality policies. Both were arguably using the report to push an agenda, and both were arguably primarily concerned with creating a favorable climate for increased broadband competition.

Unfortunately, we’ll have to wait until 2019 to see which approach the data supports.