Is Satellite Internet Good Enough to Bridge the Digital Divide in Rural Areas? According to a New Report From the FCC, the Answer Is “Yes.”

The FCC’s 2018 Broadband Deployment Report has been raising eyebrows in Net Neutrality circles thanks to its move to classify satellite providers as fixed broadband — in spite of ongoing latency and pricing issues with satellite technology.

Are you a journalist or researcher writing about this topic?

Contact us and we'll connect you with a broadband market expert on our team who can provide insights and data to support your work.

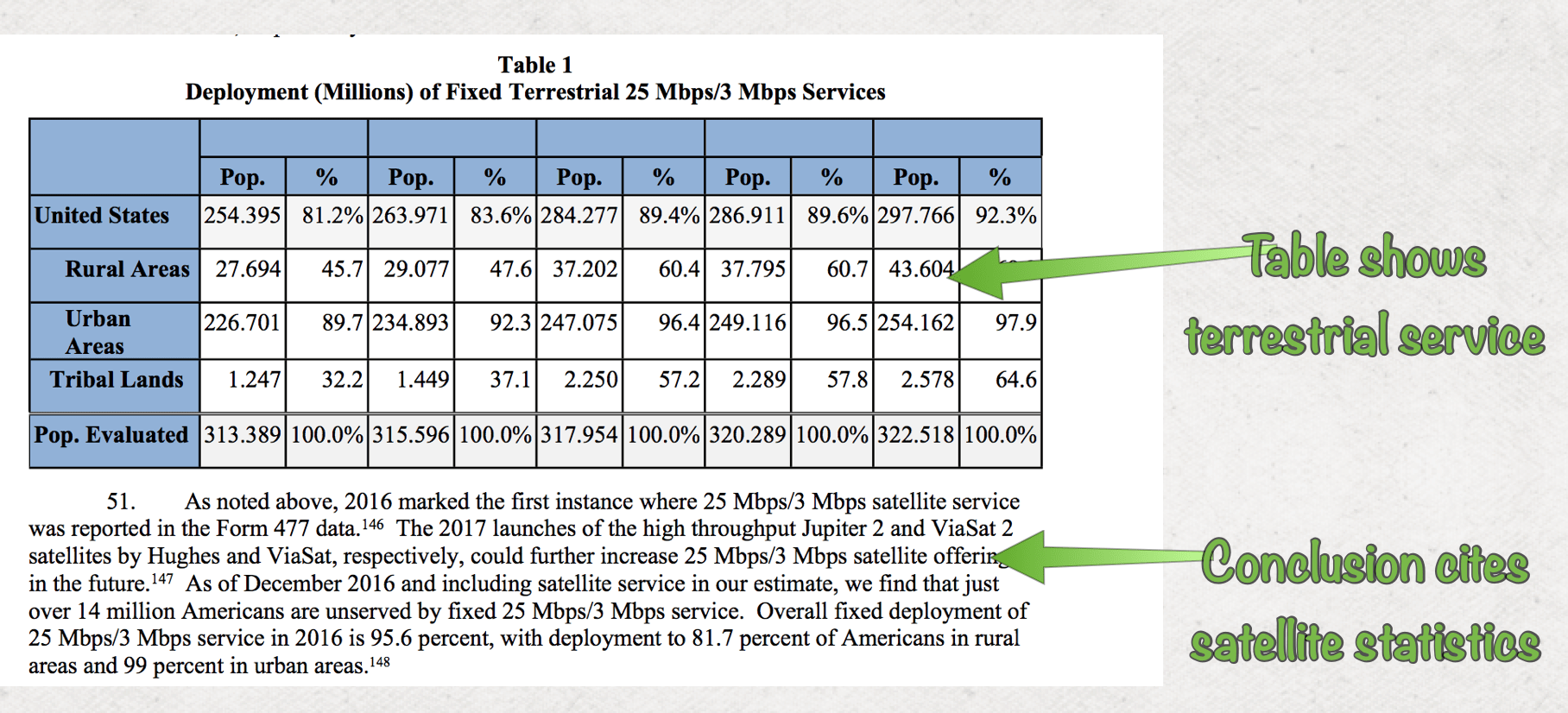

The report is contested on the partisan line since including satellite in the statistics makes it appear that only 14 million Americans don’t have broadband access (25/3 Mbps fixed and 10/3 Mbps LTE). Without satellite Internet coverage, that statistic nearly doubles to 25 million.

The media response has been pretty standard: the left presents it as pandering to ISPs. The right is largely treating it as a chance to promote the benefits of deregulation.

Unfortunately, including satellite in service statistics isn’t just rhetoric. It results in higher than usual statistics regarding the amount of the US that is considered “served” by high-speed Internet connectivity, which in turn impacts how the FCC distributes network funding for low-income communities.

In this analysis we’ll look at where satellite stands today in terms of performance and pricing, and whether or not it makes the grade for bridging the digital divide in rural America.

Is Satellite Internet Good Enough for Modern Internet Use?

When advising consumers, we generally steer them away from satellite for the following reasons:

- Limited data allowance (caps around 10–50MB/month.)

- High pricing compared to cable, DSL, and Fiber.

- Long minimum contracts. (Usually 2 years.)

As discussed above, the FCC conclusion on this point is contested and closely tied to Net Neutrality/Internet Freedom debates.

While contract length isn’t discussed at length in the FCC’s reports, the other two points are touched on, if only in footnotes.

Should “Latency” Be a Broadband Benchmark?

As it stands, the FCC uses only two metrics to determine fixed broadband quality: download speed and upload speed.

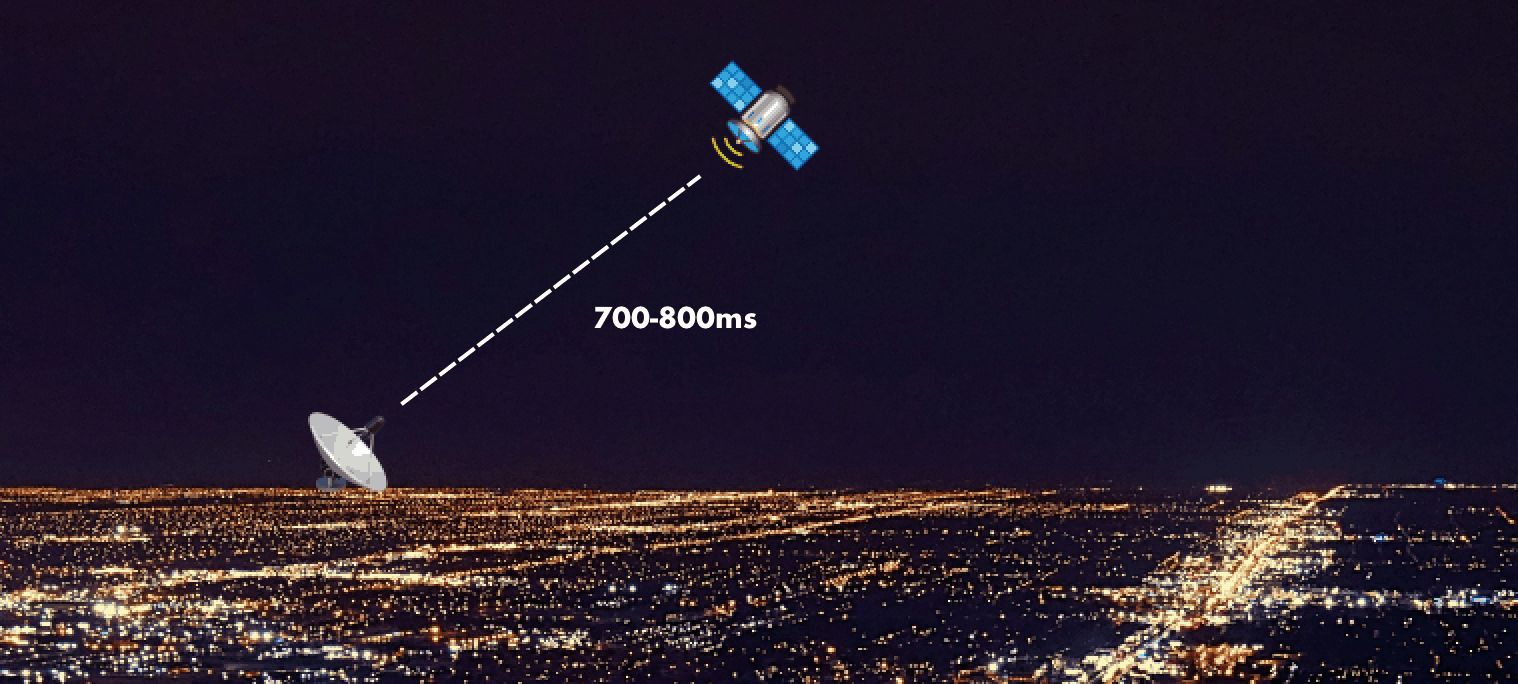

The issue of latency, or “ping,” is left out.

This matters because the FCC broadband definition currently requires fixed service to provide a minimum of 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload.

By this definition, satellite has just recently been able to meet the minimum. Both major US providers (Hughesnet and Viasat) launched major satellite upgrades in the past couple years. Satellite data has been included in Broadband Report statistics since 2016, but this is the first year that satellite exceeded the minimum broadband speed benchmarks and meaningfully impacted service statistics.

To address this issue, it was expected that the FCC might introduce latency as a factor now that satellite is often meeting or exceeding those minimum speeds. However, the 2018 report under FCC Chairman Ajit Pai declined to do so.

On page 16 of the report, the FCC sides with commentary by Internet providers, which suggests that latency is a non-issue for common consumer uses like watching YouTube:

NTCA argues that some types of broadband, such as satellite, may not meet a particular latency target and should be excluded from our section 706 analysis. By contrast, ViaSat objects to any latency standard, arguing that the Commission should not single out latency among all the performance characteristics that affect the end-user consumer experience. Verizon and CTIA also oppose adoption of a latency benchmark, urging the Commission instead to focus on consumer needs and experience. … We [FCC] decline to adopt a latency benchmark.

Should Pricing and Data Caps Factor Into Coverage Reports?

The 2018 report is equally dismissive of the need to consider how pricing affects consumer access to advanced Internet service. Again, the FCC report sides with Verizon’s comment submissions on the issue:

While factors such as data allowances or pricing may affect consumers’ use of advanced telecommunications capabilities or influence decisions concerning the purchase of these services in the first instance, such considerations do not affect the underlying determination of whether advanced telecommunications capability has been deployed and made available to customers in a given area. Thus, we believe such factors are extraneous to the present inquiry. In any event, as Verizon points out, to the extent that providers offer different types of data plans or pricing offerings, this range of choices for consumers “underscores how robust broadband deployment has been.”

While the pricing for satellite Internet plans is similar to Internet-only plans from cable and fiber providers, we generally steer customers towards wired options when they ask.

The reason for this is mainly the data caps used by satellite Internet providers. These data caps are perfectly reasonable considering the bandwidth limitations of satellite technology, but the limitation to 10, 20, or 50MB per month is often too little to serve a family home that wants to use modern applications such as Skype, or stream entertainment with a Roku. That said, they can be perfectly serviceable for basic access, use by children doing research and homework, etc.

Practical Internet Access: Are Two-Year Contracts an Access Barrier for Low-Income Consumers?

Finally, the elephant in the room that somehow didn’t get air time in this report: multi-year contracts.

As of 2018, the minimum contract length available from a residential satellite Internet provider like Hughesnet is two years.

Again, this isn’t entirely unreasonable considering the economics of the satellite business. Providing service is expensive, and they have difficulty making money off short-term customers.

That said, minimum contracts can be a significant barrier for low-income customers who likely live in rental or short-term housing. Unlike wired broadband more common in major cities like Los Angeles that can be activated on a monthly basis with a self-install box, satellite involves expensive dish equipment, complex installation with a dish in the yard, and expensive Early Termination Fees for customers who break the contract. According to broadband consultant James Webb, “if it weren’t for the data caps and minimum contracts we’d have no problem recommending it [satellite] for consumers. For now, we almost always suggest wired options like DSL and cable.”

For these reasons, many Digital Divide groups consider satellite to be a problematic solution to broadband inequality.

Left vs Right: Where Politics and Data Collide

As we’ve reported before, Broadband Deployment reports and other “fact sheets” from the FCC usually have more to do with left/right commissioner disagreements than with actually open-sourcing data about broadband adoption in the US.

The 25/3 Mbps speed benchmark, for example, tends to change with administration changes rather than consumer Internet expectations. Obama-era regulations were responsible for the current 25/3 Mbps benchmark, and the Trump-era FCC proposed lowering speeds needed to “serve” consumers within their first year in the office.

Regardless of where you stand on broadband regulation, it’s important to remember that FCC presentations of data are strongly colored by the party in power.

Satellite Internet speeds are improving, but DSL is usually better for rural customers

It used to be easy to say “only get satellite Internet if you have to.” Now that the speeds have increased thanks to launches like Gen 5, it often beats DSL in terms of speed. Meanwhile, DSL networks are getting upgrades extremely slowly due to the high cost of replacing the lines with fiber optics. Choosing a rural Internet provider comes down to location, more than technology.

Future-facing analysts often cite Elon Musk’s low-orbit satellite mesh project as a beacon of hope for lowering cost and boosting performance of rural broadband. The question is, at what point will the price and logistics of service compete directly with wired service?

It’s a question satellite companies and telecoms are rushing to answer, since untapped customers are untapped revenue streams. The situation was well summed up by satellite industry consultant Tim Farrar in a statement to Quartz: “How much cheaper does it need to get? That’s the multibillion dollar question.”

For now, the FCC seems to be moving to call the existing services “good enough,” in keeping with the light-touch approach to telecom regulation. Whether or not this low-pressure approach drives innovation in the consumer broadband market or not remains to be seen as 2017–2018 data becomes available early next year.